Gippsland Highlands

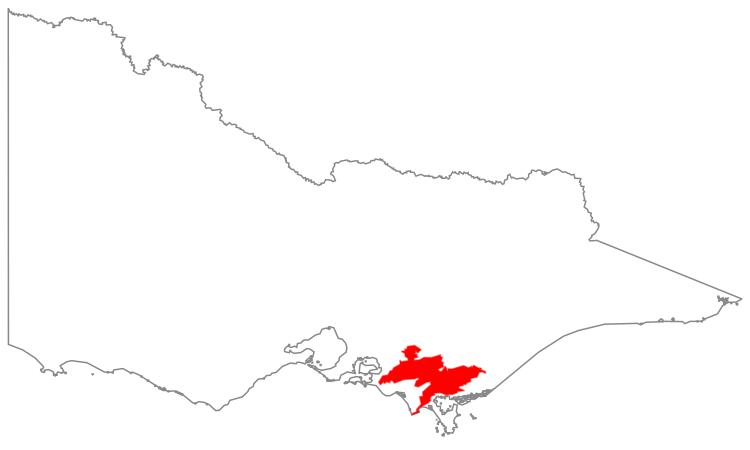

Location

The boundary of this region approximates the 150–200 metre elevation contour interval and so includes the Strzelecki Ranges. These ranges are an example of block mountains and, as such, are largely defined by the various geological faults (refer Hills 1940). This region is completely surrounded by the Gippsland Plain.

Major grids P and T. Approximate area 2232 km2.

Major landforms

The present-day physiography of the region is a consequence of erosion of differentially uplifted blocks of late Mesozoic sediments (existing now as sandstones, mudstones and black coal). In places the Mesozoic sediments are overlain by more recent sediments (sands, gravels and brown coal) and lava flows (principally along the Morwell–Leongatha axis). The uplifted blocks have been weathered and strongly dissected, such that the resulting landscape is smooth and rounded (closely resembling that of the Otway Range). The nearly symmetrical V-shaped valleys often have very steep sides, commonly reaching 40°. Details of the geological history of the region are given in Anon. (1972b, 1980b), Douglas (this volume) and Jenkin (1971). The highest point in the region is Mt Tassie (740 m), with Mt Fatigue (586 m) and Mt Worth (518 m) the next highest points. The soils of the region are predominantly fertile loams and earths (Gibbons and Rowan, this volume).

Climate

The region experiences a temperate climate with a predominantly winter rainfall maximum typical of the southern Australian coastline. Mean annual rainfall varies from about 900 to at least 1400 mm, with the wettest months usually being from May to October. Most of the rain-bearing winds are westerlies. This results in a rain-shadow zone to the east of the Strzelecki Ranges (Anon. 1980b). The temperatures are relatively mild throughout the region. Topography has a considerable influence on temperature. Higher elevations in the region have lower maxima and minima than localities at lower altitudes. Typical mean daily maxima range from 11°C to 24°C, with mean daily minima ranging from 2°C to 10°C. July is the coldest month, and February the warmest. Frosts are relatively frequent, especially in valleys. Snowfalls occur two or three times a year on the highest areas of the region. See also ‘Climate of Victoria’ (this volume).

Vegetation

Most of the native vegetation of this region has been cleared for settlement. In many areas, the native plants have been completely replaced by alien pastures, crop plants, and weeds. There were once strong similarities between the floras of this region and the Otway Range, but this region has now lost far more of its native vegetation. For example, fern gullies now exist only in a few isolated localities. Remnants of the pre-European flora are scattered, and frequently are significantly disturbed.

Forests

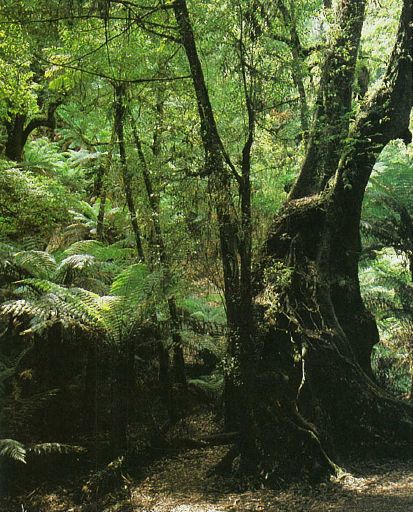

Cool temperate rainforest

A closed-forest dominated by Nothofagus cunninghamii occurs in deep, protected gullies within the high rainfall areas of the region (Howard & Ashton 1973; Gullan et al. 1984; Seddon & Cameron 1985a, 1985b). Atherosperma moschatum occurs as a sub-dominant or understorey species, together with Acacia dealbata and A. melanoxylon. Dicksonia antarctica is the most common tree-fern, but Cyathea australis and C. cunninghamii are also common. The trees and shrubs of the understorey include Bedfordia arborescens, Coprosma quadrifida, Hedycarya angustifolia, Lomatia fraseri, Olearia argophylla, O. lirata, Pittosporum bicolor, Pomaderris aspera, Polyscias sambucifolia, Rapanea howittiana and Tasmannia lanceolata. Common lianas include Billardiera longiflora, Clematis aristata, C. glycinoides and Parsonsia brownii. The ground-layer is generally sparse under the closed canopy. It is dominated by Fieldia australis (often an epiphyte), with Australina pusilla, Sambucus gaudichaudiana, Tetrarrhena juncea and Viola hederacea being common. The diverse fern flora includes terrestrial and epiphytic species. The common ferns include Asplenium bulbiferum, Blechnum fluviatile, B. nudum, B. wattsii, Grammitis billardieri, Microsorum pustulatum, Polystichum proliferum and Pteridium esculentum (particularly in disturbed areas) (Gullan et al. 1984). Rainforest remnants occur in the Tarra–Bulga National Park (Plate 6b). An ecotonal closed-forest that has elements of wet sclerophyll forest and cool temperate rainforest occurs in environments that are intermediate between the two communities.

Wet sclerophyll forest/damp sclerophyll forest

Eucalyptus regnans dominates a tall open-forest on deep, loamy kraznozem soils, on wet highland slopes. This community is much less common in the region than it used to be. Extensive clearing by the early settlers, timber utilization and the devastating bushfires of 1898 and 1939 have resulted in few mature stands remaining (Gullan et al. 1984, 1985). E. obliqua and E. cypellocarpa are often co-dominants or associated species of this community. The understorey and ground layer species include Acacia dealbata, A. melanoxylon, Australina pusilla, Bedfordia arborescens, Cassinia trinerva, Clematis aristata, Coprosma quadrifida, Hedycarya angustifolia, Olearia argophylla, O. lirata, O. phlogopappa, Pandorea pandorana, Parsonsia brownii, Phebalium bilobum, Poa labillardieri, P. sieberiana, Pomaderris aspera, Prostanthera lasianthos and Tetrarrhena juncea (Plate 6c). The understorey tree-ferns include Cyathea australis and Dicksonia antarctica, with Blechnum nudum, B. wattsii, Calochlaena dubia, Histiopteris incisa, Polystichum proliferum and Pteridium esculentum forming the ground-layer ferns.

An open- to tall open-forest (damp sclerophyll forest) commonly occurs on well-drained, sandy loam soils in flat to undulating country of this region, and extends into the neighbouring Gippsland Plain to the south. This community is extremely variable, both floristically and structurally. The dominant eucalypts include Eucalyptus consideniana, E. cypellocarpa, E. obliqua and E. radiata. The understorey is commonly dominated by Acacia dealbata, A. mucronata, A. verticillata, Billardiera scandens, Cassinia aculeata, Epacris impressa, Gahnia radula, Gonocarpus tetragynus, G. teucrioides, Goodenia ovata, Lomandra filiformis, L. longifolia, Platylobium formosum, Pomaderris aspera, Pteridium esculentum, Pultenaea juniperina and Tetrarrhena juncea. Examples of this community occur between Boolarra (Gippsland Plain region) and Mirboo North.

Woodlands

Leptospermum myrsinoides heathy woodland

This community is more common in the neighbouring Gippsland Plain, but occurs in this region in areas with sandy soils and mean annual rainfall 700–900 mm. The shrub-layer of this community is always dominated by the dense shrub Leptospermum myrsinoides. The tree-layer is usually well-developed and results in a woodland with a heathy understorey. Eucalyptus consideniana, E. pryoriana and E. radiata are the commonest tree species. The shrub-layer is typically dominated by sclerophyllous shrubs, such as Aotus ericoides, Dillwynia glaberrima, Epacris impressa, Hibbertia acicularis, Leptospermum continentale and Monotoca scoparia.

Land use

Since the destruction of most of the wet sclerophyll forest, damp sclerophyll forest has become the most heavily utilized community for timber production and allied forest products (e.g wood-chips) (Gullan et al. 1984, 1985).

Hardwood and softwood plantations are now being established on previously cleared areas. Eucalyptus regnans and Pinus radiata are the two most commonly planted species. The region is important for recreation. Much of the region has proved to have low potential for agricultural development; however, dairying and beef production are important primary industries.

National Park

- Tarra–Bulga—1520 ha.

State Park

- Mt Worth—1040 ha.